- Home

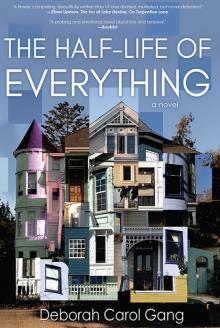

- Deborah Carol Gang

The Half-Life of Everything Page 3

The Half-Life of Everything Read online

Page 3

As Jane talked softly, he realized that it was her voice that got him. It had been years since he had heard Kate’s normal cadence, but here it was, the slightly fast pace, not because she was in a hurry but, in case you were, the slenderest of an East Coast accent now layered with Midwest, and slightly formal vocabulary. He listened to Jane patiently offering new dates and times and didn’t open his eyes until she ended her call.

He cut off her apology with effusive thanks for her help. They made plans to talk in a week and then he left, first stopping by Kate’s room, where she was napping. He watched her for a moment. The blond prettiness that often faded so early had staying power in her case. Her skin was sturdy for a blond. Of course, now that she was ill, she did fade to something close to plain. Beauty depends so much on alertness. She was sweating lightly from the sun, which was striping the bed through the half-open blinds. He shut the shades quietly, then left for home.

CHAPTER FOUR

The next time he went to see Kate, he went straight from work without taking a walk first because he didn’t want to use up the daylight. When he found her in the library, he took her hand and said, “Let’s go out back for a while. It’s plenty warm.” She didn’t speak and braced herself in her chair, an unpredictable resistance that had appeared recently. He sat with her for a few minutes. Christ, I’ve been inside all day on a perfect day and I do not want to sit in here. He waved in the direction of the closed circuit camera and mouthed “outside,” kissed the top of Kate’s head, and went out back to one of the benches they liked. “They” liked. He didn’t know what Kate liked anymore.

It was a bench he liked, yet his sensibility about benches came from Kate, who would point out what made a bench welcoming, which materials felt nice to the touch, how benches in a corner or at an angle felt more inviting. When the kids were little, the four of them could make an adventure out of a walk to one of Kate’s favorite benches. Kids are happy with so little. He positioned the paper he’d brought, a day-old Times that he was determined to get through, but then put it down after the first article, preferring to watch the birds torment the squirrels.

Soon, the cats would wander by to be harassed by the squirrels, plot lines not unlike the article he had finished. A shadow fell over him. “Hi, David, I thought I recognized the back of your head.”

He jumped up to greet Jane just as she sat down. They both started to move and he said, “Stop. I will slowly sit down and stay there.” They laughed and settled in. Jane was wearing a not very sensible skirt, a “going-out skirt” as Kate would say, meaning not for school conferences or jury duty. Instead of her usual blazer, she was wearing a sweater that wrapped and tied and maybe dipped lower than she realized. He imagined she had a date after work with a husband or someone newer—the jewelry on her left hand was ambiguous. He had a thought of envy, a now common emotion for him that he was skillful at setting aside. It wasn’t anyone else’s fault. She arched her back slightly to pull her cell out of her pocket, glance at it, and put it away. He looked and then looked away.

“I’m making progress on the insurance situation,” Jane said, “despite the fact that yesterday one clerk said the problem was that Kate had moved to another facility.”

David laughed. “Well, that sounds like progress, all right.”

“Oh, if I get an idiot, I just thank them and hang up and call back. You never get the same person twice. The next person straightened that part out. You can be sure your wife still resides here.”

“Thank you,” David quietly said, thinking how strange his life had become that someone taking care of him, just a little, could almost make him cry.

Jane continued, “I don’t know if it helps you to know that this is one of my favorite assisted-living centers. I know a lot of that is about money—that it’s so well endowed and doesn’t have to be fully self-supporting, at least not for the building and the grounds and all that. You’re lucky.”

“Yes, I’m very lucky.”

She turned to him and said, “I’m sorry. That was so stupid. I don’t usually say dense things like that.”

“It’s okay. I am definitely grateful. And there is some luck twisted inside that. Please, let’s talk about something else. Do you know how to talk about movies?”

She did, though she was one of those people who wait and watch movies at home, so first they discussed the virtues of Netflix versus Redbox versus On Demand, and now streaming (which he didn’t understand at all and understood no better after her explanation), while he put in his plug for seeing movies in big theaters. She made him concede that sitting next to a two-pound box of popcorn is not a good smell. And people talk too much. They came up with enough titles they had both seen to keep things going for a while.

He found he missed his sons more than he missed Kate. The memory of Kate’s fast, smart mind was too faded, but the boys would enjoy this. They talked until sunset, though not only about movies. “Tell me more about your work. Tell me about someone you helped today,” he suggested.

She told him in a general way, of course, about the man who thought his wife’s dementia was willful—a punishment for undisclosed things he had done which hurt her.

“And how do you help him?”

“I don’t argue with him. I say, ‘You wish you could go back and change things,’ and then he cries. We do that every week. He says it’s the only peace he has.”

They let a silence sit between them and then Jane said, “Teach me some history.” He suggested she pick an era. “All of the above,” she said, seriously. “None of it ever took in school.” He thought how odd to meet another smart woman who, like Kate, had only the vaguest sense of the past.

“Try World War I,” she suggested. “It still seems like a silly reason for a war.”

“All wars are silly,” he countered and then began to lay out the background, which nearly everyone seemed to have missed in high school.

She listened carefully and, when he found a good stopping place for the first installment, she said, “Why do you like history so much? I know it’s endlessly interesting, but why did you choose it?”

“The usual reason—I had a phenomenal teacher in tenth grade—but also because it’s over. You’re not waiting for the other shoe to drop like you are in life. And, theoretically you can learn from it, although almost no one ever does.”

She smiled at that and said, “Maybe too few people even remember what happened. Like Watergate—I know it was a huge event, but I don’t really understand it.”

“You realize that you lived through Watergate, right?”

“Be nice. I was like ten when Nixon resigned.”

He was well practiced at being kind about people’s ignorance—it was the only way to teach. He wasn’t sure if Kate would have known anything about the Korean War if not for M*A*S*H, but he had always answered her questions without betraying his amazement.

Jane looked at her watch. “I need to sprint to my next meeting, but I’ll remember what you’ve told me—unlike high school. I’m really a much better listener now.” She stood and walked backwards a few steps before saying, “We can cover Watergate next time.”

Dylan pulled up in front of Jack’s off-campus house. It was a dump, the kind you could enjoy if you were sure you’d never live that way again. As he climbed the stairs, Dylan mentally counted four couches, plus one standing on its side. Jack came through the front door fast and they almost slammed into each other, then turned it into one of those body bumps that pass for hugs. Anyone would recognize them as brothers, with Jack slightly broader and slightly taller, with hair a shade more blond. Two guys leaving the house looked at Dylan and jumped a little when they saw Jack just off to the side. One of them said, “I’m seeing double,” and they all laughed.

“What do you think, Dylan? A little different from the freshman dorm?”

“Definitely. You gotta live this way once.” He peered past the screen door into the living room with yet more derelict couches and three TVs o

f various sizes, all huge. They went inside and sat, moving pizza boxes and game controllers aside.

“You always had those grownup apartments with one roommate—or no roommates. What was that about?”

“With what was going on with Mom,” Dylan said, “there was no way I wanted any more chaos. Plus, I knew I had to study. Can you imagine leaving Dad like that to go to school and then screwing up? Like things weren’t bad enough already.” He cracked a knuckle, a habit he thought he’d lost. “Mom was together enough then, at least through my second year, that she came along a few times to visit. So this kind of scene wouldn’t have been good.”

“Kind of embarrassing too—with a lot of roommates around and their girlfriends, judging her and all.”

Dylan admired how Jack just said things. He’d admit to petty, unflattering feelings and then you’d realize, well okay, the world didn’t collapse. “Yeah, I hate people thinking that’s who she is.”

“You know, if you’d had a place like this back then, the shock could have snapped her back to her real self, like in that movie, the really old one on TCM.”

“Snake Pit,” Dylan said, pleased that Jack remembered. “You know, our real mother would have come here once to see the place and, after that, called you from the car.”

“Or redecorated.”

Jack took him on a tour of the seven bedrooms, one illegal. The larger rooms had yet another couch opposite a bed or futon. There were fans and space heaters—the largest bedroom had one of each going. The bathrooms sported layers of soap scum, dried shaving cream, and black deposits around the sink. Dylan almost asked Jack how he kept his contact lenses uncontaminated.

Along the tour, he was introduced to various groggy housemates. At least three had the same first name—he would wait to hear the distinguishing nicknames, which he knew could be as benign as Jersey Dan or as suspect as Tether Mike.

In the kitchen, which was surprisingly close to clean, he decided that he’d ask Jack if people stripped the batteries from the alarms and, if so, whether he and Jack should go to the hardware for more. There’d been a fire at an off-campus house where his dad taught.

Later, while they were seated in a restaurant waiting for their competitively large breakfasts to arrive, Jack testified that the smoke alarms were all operating—the landlord had switched to hardwired, so it wasn’t even a temptation. He didn’t ridicule Dylan for asking. One of the boys who had burned to death had been a year ahead of Jack—also a soccer player. They sat not saying anything for a moment.

“How do you think Dad’s doing?” Jack asked.

Dylan shrugged and said, “Think he’ll ever remarry?”

“He never seems happy or unhappy. Just blah.” Jack opened and shut the menu. “But I don’t see him much now. Why do you say that? About remarrying.”

“Can you really see the guy living the rest of his life like this? Taking care of someone who doesn’t know him? I don’t think I’m going out on a limb to guess that they haven’t had sex—who knows for how many years.” He thought he saw Jack blush.

“Well, do you have a plan or something?”

Dylan laughed. “No, little brother, I don’t have a plan. I’m just asking.”

What Dylan really wanted to ask was why Jack never seemed to have an actual girlfriend—someone the family could meet. He used to think that Jack was just doing what good-looking, confident guys do: revel in seduction and excess and … delay the routine of a relationship. Or maybe Jack, like him, was afraid of being in love. Besides, love leads to loss—not always, but a lot. Well, he sure wasn’t about to bring the topic up now.

It wasn’t like he had any of it figured out.

CHAPTER FIVE

“I don’t consider myself a paranoid person,” Jane said, “but I really think that some people are staring at me. At us. Do you know everyone here?”

“No more than thirty percent,” David said. “I know they’re staring. I want them to because I have to ask you something—and staring will be part of it.” He didn’t doubt the affinity he detected between Jane and him. Despite his many years of fidelity—or maybe because of them—he knew that attraction traveled mysteriously through space, no matter how camouflaged by politeness or rudeness. There were just too many tells.

He saw an earlier, braver version of himself at not quite twenty-five, as he entered a noisy smoky party and saw Kate across the room, backed against the wall by a large, loud drunk standing too close. She was trying to sidle away towards open space, but the drunk moved too, talking, almost yelling about how his father wanted him to join the family business but he wanted to prove himself first. As David approached, the drunk punched her arm too hard, saying, “You get my meaning, don’t you, Kate,” and David interrupted him with, “If you’re Kate, you’re wanted out on the porch.”

As the drunk turned, David got between him and Kate and she moved quickly. The outraged drunk said “hey,” but was too slow to react as David followed her, weaving through the crowd to a corner of the porch. She caught her breath for a moment, and then told him she was drunk too, and she was going to kiss him one time, but then they’d have to be properly introduced. And she did kiss him, and he could tell she wasn’t drunk at all. Or just enough to kiss a stranger and sing, “Yes, I’m certain that it happens all the time” and he surprised himself by whistling, almost perfectly, the preceding line.

And now he was in a coffee shop with a woman named Jane because talking to Jane was the only time he felt like himself—the only time he could get enough air into his lungs. If he was married, then what he was about to do was wrong. But was he married? Married in a way that bound him beyond finances and caretaking? It’s called ambiguous loss, he’d learned, but really it just felt like loss—the regular kind. He and Kate had lived together without being married—no small thing at the time. Now they were married without living together, and he was sitting here with a woman he didn’t know. He might be about to ruin what he had, but he was closing in on fifty-seven and his life was a twisted fairy tale, like Sleeping Beauty without the good ending. In a flash, he’d be old.

“Okay,” Jane said, giving away nothing. “Ask.”

“Do you want to go out sometime? And I don’t mean to discuss insurance.”

“You mean like a date?”

“I mean do you wanna hang out sometime?” He hoped he sounded like a man who knew how to flirt, despite decades of avoiding it.

She laughed. “You can really tell which of us works with young people.”

“I promise never to say ‘dude,’ and I have no tattoos. But people will stare. I am that car wreck on the side of the road.”

“Good to know all of this, especially the tattoos, but those aren’t the things I’m worried about.” She glanced around. “For today, let’s just go over the insurance like we planned, and then I’ll think and you’ll think.”

“I’m okay with that.” He’d said his piece and that was enough for now. He thought about his notoriously terrible Monopoly skills—terrible because he always wanted everyone he loved to come out equal. He would encourage the kids or Kate to buy certain properties to protect themselves and it never worked—one or more of them, including him, always lost big. He wanted everybody safe, and they wanted to have fun. He might be about to ruin what he had, but he had learned that nothing was safe.

Jane reached into her briefcase and brought out papers and her summary, written in “plain English for the normal middle-aged brain,” as she put it.

“The L has agreed for now to stop billing you for the balance,” she explained. “You need to sign this request to appeal the decision of the company that quit paying. I think they know they’re primary and should be paying first, but the lower-level staff doesn’t have the authority to reverse the mistake.”

She managed to sound lawyer-like but flustered, too. She gestured at one point, knocking over the remains of her latté. He helped her clean up and their hands touched. After the third touch, he put his hands in hi

s lap. “I know you didn’t have to help, and I would have slogged through it somehow, but thank you.”

He looked up to see a neighbor and the chair of the Poli Sci department watching him. He smiled and waved as they glanced away.

“I know I’ve missed a couple of visits.” David apologized to Kate’s unreadable face and immediately felt ridiculous for it. He went on. “I was at the annual trophy hunt in Chicago.” A small contingent went each year to recruit grad students, preferably a few from the Ivies. He started to describe his favorite prospect and then stopped. He always felt he had to say something to her, and the list of things that weren’t ridiculous was very short, but still, what was the point? Recently, he had begun reading when he was with her and she didn’t seem to mind. She was more remote and blank than ever, but at least he could get caught up on his newspaper. After reading for an hour, he said goodbye and went to find Jane. If she wasn’t alone, he’d say he needed to show her the most recent letter from his insurance company, the one that completely contradicted the letter that came before.

While he waited by the antique double desk that served as a workstation, he studied the three monitors, imagining as usual that a panel of judges was rating his performance as loyal, caretaker husband.

He saw a figure down the hall leave a resident’s room and jumped away from the desk. A staff member he didn’t know approached him.

She knew him. “What can I do for you, Mr. Sanders?” and when he told her, there was the slightest hesitation before she said, “Jane’s not assigned here any more.”

The words didn’t sound like English to him. He understood each word, but the meaning didn’t seem possible. Why would she leave without telling him? She ran her own business—no one could make her leave.

The Half-Life of Everything

The Half-Life of Everything